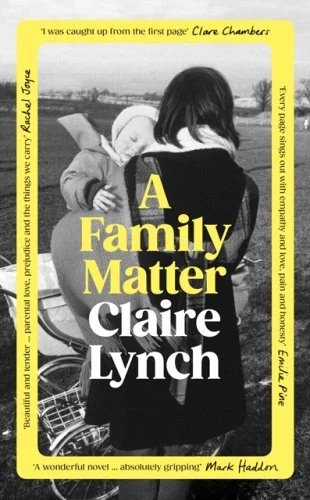

Claire Lynch’s A Family Matter is set to be THE conversation-starting book club read of 2025. At once heart-breaking and hopeful, it asks how we might heal from the wounds of the past, and what we might learn from them. To celebrate publication, we’re delighted to share a powerful letter from Claire about the very real and recent history behind the fiction, and an extract from this unmissable debut.

A note from the author, Claire Lynch:

Dear Reader,

At book groups or events for my memoir Small, the story of how my wife and I had our children, I met women who were keen to tell me about a different generation of queer mothers. Some of these women would wait until the event was almost over, finding a moment to catch me alone just before I left. Others would bravely put up their hands, sharing their experiences with the whole room. Women only ten or twenty years older than me reminding me that the happiness I was describing within my family, the hope I felt, was really a question of good timing.

I was ashamed of myself for not knowing these stories, for not understanding a history that could have been mine. In the years that followed I searched for these families in community archives, in newspapers, in PhD theses, and in court papers. I read their stories, and I cried over them. One piece, the cover image from OUT magazine, April/May 1977, spoke to me so powerfully that I printed it out and pinned it to the wall above my desk.

The image shows a mother holding a small child as the combined strength of her husband, the police, and a judge try to pull them apart. In the associated article, a lesbian mother describes packing a suitcase for her three-year-old daughter. As she packs, the mother keeps up the pretence of a normal bedtime routine, knowing that in the morning the child will be taken from her and sent to live with her father and grandparents under their legal custody. The article is a plea to be heard, to be understood.

The more I researched these cases, the more prevalent I understood them to be. I learnt that 90% of the lesbian mothers in the UK who faced this kind of divorce case in the 1980s lost legal custody of their children. Exact numbers are almost impossible to trace since most mothers, knowing the likely outcome, didn’t even get as far as the courtroom.

Now I knew. I understood precisely what had happened to mothers like me. I knew what was said by politicians in the Houses of Parliament, by columnists in newspapers. I had read the transcripts of judges and barristers and social workers. What I didn’t know, of course, was what people said privately over kitchen tables, what they thought and felt and hoped as they fell asleep each night.

Through the characters in A Family Matter I have tried to let myself, and I hope, the reader, imagine that part. I have tried to forget the statistics and to think instead about what it would have been like to live through this, and to wonder what might happen next. The novel takes place in a quiet British suburb where people act, as people almost always do, according to the rules, unwritten and otherwise. I am deeply attached to every single character in this book because, whatever the consequences, they do what they believe is best. I think of A Family Matter not as a story about historical prejudice, but one shaped around good intentions.

I have lived through both of the time periods in which the novel takes place, 1982 and 2022; the first as a daughter, the second as a mother. Dawn’s story is not my own, nor is Maggie’s, but I have been profoundly changed by living alongside them in the writing of this novel. Thank you for reading it.

Claire

An extract from A Family Matter

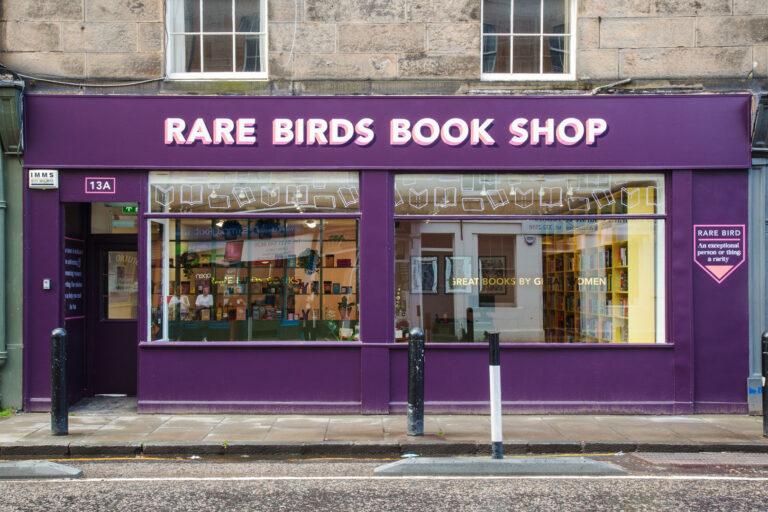

She arrives in Euston to wet-leaf pavements, to the darkness of a November afternoon which might as well be night. She plays the role of a woman looking in a bookshop window, hands deep in pockets, chin tucked into the hiding place of her mohair scarf. If she is seen here she will say, I was just window-shopping. I thought it was just a bookshop. A normal bookshop.

The sign on the glass door panel is turned to closed, but Dawn can see the light in the back room, yellow and glowing. The shapes of women, arranging chairs, passing mugs. Her reflection in the glass is strange, like a statue, like a ghost. She shakes her hair, this weather is a disaster for curls, she stands up straight. She has made an effort, best earrings, newish coat. Armour to keep her safe. Dawn watches the woman walk towards her through the darkness of the closed shop, turning the latch to open the door, letting in the air from the cold street. The woman, tall and smiling, who says, ‘Are you coming in?’ Before she leads Dawn gently by the elbow, past the shelves of other people’s stories.

The room at the back of the bookshop is small and the women sit knee to knee. The first time she joins them Dawn does not speak. She nods her head and holds her herbal tea close to her face, letting the steam warm her cheeks. She tries not to stare at the two women sitting opposite, the quiet way they hold hands, the way they look at each other. The woman beside Dawn is wearing suede boots, dark green, baggy at the ankle, the perfect heel. Dawn has seen them in the window of Russell & Bromley. Her name is Sue, she has two sons. She only went to court, she tells the group, to get the children away from her husband, who turned out to be the type to hold your hand to the kitchen table and use your forearm as an ashtray.

The other women listen, they let her talk, and Dawn wants them to be more surprised. She wants someone to call the police, someone to do something when Sue says, ‘His lawyers said we were dressing them up as girls. Putting ribbons in their hair. The judge didn’t want to hear a word of what he’d done to me.’

/

Dawn comes back to the group the next week and the next. She learns about the never-ending battles with social workers, the cost of solicitors’ letters. She listens to the women who strike deals with husbands, the ones who find a way to make it work. The ones who don’t.

In the gaps between, the women share other scraps of their lives. Melanie, whose son has got into the grammar school. Caroline, who has had her first driving lesson, after all these years. It is just like every other mothers’ group Dawn has been to. Tired women, doing their best. When she listens to them she can’t understand why the courts bother, why all this effort is being used up on these ordinary women. At the end of one evening, Dawn finds Sue stacking up the chairs and asks the question that has bothered her all this time, ‘What harm are they doing to anyone?’ Sue smiles at her, pauses to find the words to break it to this young woman, the world, and what it was really like. ‘They are terrified,’ she says to Dawn, ‘that’s what it is. Think about how it looks to them. Mothers, housewives, shacking up together. We’d bring the whole system down.’

/

A solicitor comes to the group one night, a serious woman in a dark blue suit. ‘There’s more chance of salvaging something,’ she says, ‘if you can prove to the court that you live alone. Persuade the judge it was a one-off, not a lifestyle.’ She admits an out-of-court settlement is usually safest. If you’re willing to play the good girl, you might get as much as every other weekend and half the school holidays, say. If you can persuade your girlfriend to disappear at regular intervals. If you can get your husband to sign up to it, that is.

‘And if he doesn’t?’ they ask.

/

On the bus home Dawn sits next to the window, folding her ticket into a tiny paper aeroplane. All the women in the support group have told her to avoid court if she can. If he’s a reasonable man they should try to come to a private arrangement. But it is already too late. The court date is set. Heron, naturally, wants to do it all by the book. Really, she thinks, he wants someone to blame for all this fuss. Deep down, Dawn knows, her story will be different. She’s sorry for these other women, she really is, but she will explain it all, make it clear. Her love for her daughter is a kind of scientific truth, solid and measurable, anyone can see that. When the women in the group read aloud from their judgments Dawn holds her breath as if warding off their bad luck. These judges who take it all so personally, standing as the last line of defence between innocent mothers and dangerous women who might seduce them in the supermarket. Nothing about being with Hazel feels like a bad influence to Dawn. It feels like electricity.

On brighter days Dawn knows that finding the group has helped, she knows now that she is not the only one. Still, it is a risk. ‘Don’t tell anyone you’ve been here,’ Sue tells her. ‘Not even your solicitor. It will make you seem political. They don’t like political.’ It wouldn’t matter anyway. Heron has sent someone to follow her, or the solicitor has. She’s seen a man, awkward and overdressed, some clerk probably from the office, trying to look like a normal person. She’s noticed him at bus stops and in the phone box near the flat. He must have watched her, surely, going into the bookshop each Thursday and afterwards, turning the key in Hazel’s front door, pulling the curtains. Dawn’s solicitor had warned her not to move in permanently. It might look, he had said, as if she has already made her choice. But where else did they think she could go? Her friends were Heron’s friends; they didn’t want to get involved. She’d tried to stand on her own two feet. When she went to fill in the forms to apply for a flat of her own the man at the council told her to go back to her husband.

/

It had taken a few minutes to make sense of it, that day on the doorstep. Her key sliding into the lock as it always had, in, but not turning. Stiff and useless. Heron and Maggie weren’t home, that much was clear. She’d looked through the window, and the letterbox, seen that Maggie’s coat and welly boots were missing from their place in the porch. The side gate was high but Dawn thought she might be able to climb it if she used the bin for a step up. And then what? A stone through the glass of the back door? Relying on the chance that the kitchen window had been left slightly ajar? The day was already starting, the street filling up with people who would have stopped to stare at a woman breaking into her own house. Dawn had looked around, for help, or witnesses, and seen only teenagers in blazers, men in suits, walking in long strides to the station, a sandwich and a paperback tucked in their coat pockets. It would only add to the scandal if the neighbours saw her battering down the door. Dawn could already feel them watching her, waiting to see what she might do, from the safety of their semi-detached lives. Dawn didn’t huff or puff. Instead, she locked herself inside the car and made a list on the back cover of the road map of Great Britain: all the places she could go, all the people who would understand her. There was only Hazel’s flat on the list. Only Hazel.

/

The journey back from the support group feels much longer than the journey there. Dawn walks from the bus stop and imagines herself, wills herself, already home. The flat will be warm, and Hazel will be there, standing at the hob, sipping at the edge of a wooden spoon to check if the dinner is ready. This is almost it, they say to each other, almost a life. They will get through this part then they will live. They will need to find a bigger place, of course, for the three of them. Space for Maggie’s toys, her little bed.