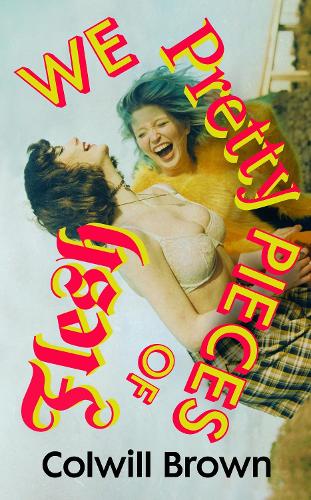

We Pretty Pieces of Flesh, the debut novel by Colwill Brown is the unforgettable story of three girls whose friendship is threatened by a devastating secret.

Set in Doncaster and written entirely in South Yorkshire dialect, it takes you by the hand and leads you through Doncaster’s schoolyards, alleyways and nightclubs, laying bare the intimate treacheries of adolescence and the ways we betray ourselves when we don’t trust our friends. Thanks to our friends at Vintage read an exclusive extract the book, below.

Victory

Ask anyone non-Northern, they’ll only know Donny as punch line of a joke or place they changed trains once ont way to London.

They’ll recall afternoon they wa relegated tut station platform for fifteen freezing minutes, warming their hands round a paper-cup cappuccino, waiting fut LNER express route to tek em off somewhere else, suspecting that if they stepped beyond station doors forra second they’d be asked by five blokes—and at least one bloke’d ask twice—Alreyt, love, you got 20p fut phone? No point venturing intut town centre, exploring place affectionately described by natives as “Dirty Donny,” and spitefully described by posher towns as “chav central,” “a scowl of scumbags,” “a collection of small former mining villages who won’t stop complaining about Thatcher,” or “home ut country’s worst football team.” Some folk reckon Doncaster boasts kingdom’s highest boozer-to-human ratio, but that’s an honour also claimed by residents of every lost borough in England.

[…]

If trains dint have to pass through it, they’d think, Doncaster wouldn’t need to be a place at all. They wouldn’t know about sleeping in cornfields under t’stars, nested in makeshift stalk beds, chatting till dawn.

They wouldn’t know about keeping a campfire burning all night int ancient woods, or tiptoeing back int morning, dodging clumps of bluebells we couldn’t bear to trample. Or spending a weekend building thrones from smooth boulders we found ont riverbank, beside waterfall’s roar and rush. Or us three perched on us thrones—sweaty, knackered, happy—pinkie-swearing we’d always have each other’s backs.

They wouldn’t know about us parents, time they sang and hugged and cried, dancing ont sofa till four int morning, night Tony Blair’s Labour Party got elected. About hope us parents held forra fairer future: things can only get better. About all of us, how loud we laugh, how sharp we feel, how hard we love, how soft.

And they wouldn’t know about Donny’s still visible chunk of Roman fort, but to be fair, neither did we. We dint recognise eighteen-foot stretch of weathered stone for warrit wa, mossed and grassy, thicker than a body is long. We dint feel centuries beneath us chilly bum cheeks when we bought two litres of cider, spent afternoon sat on that wall gerrin pissed in us Adidas Poppers. We dint imagine soldiers in leather sandals fighting battles wi their irontipped javelins. We wa too busy fighting us own battles.

Remember when we wa so young, we dint even have run ut whole town yet, when big school warrus universe, when slightest victory med us feel invincible, like as long as we stuck together, we could tek on any fight and win—like time us PE teacher said we had to play football wit lads, even though there wa only three of us and sleet screamed across school field like a fleet of angry bees. Sight of it from window med chills run through us, even int warmth ut changing rooms. Lads’d had their growth spurt by then; they all wore shin pads and spiky football boots. We just had us Reeboks, shorts, unpadded shins, naked knees. They jeered when they heard us begging Sir to lerrus off: S’up wi yas? They said. Are you ont rag, like? But Sir wouldn’t gi us special treatment just because we wa lasses. We dint see why Sir got to decide whether we gorrus teeth kicked in. We dint understand why we weren’t allowed to say no.

We decided we’d play in goal together, three of us in a row. But when we gorrup top field, wind pelting ice pellets at us cheeks, goal hanging ovver us like a giant staple, we realised we’d volunteered oursens fut bullseye. We linked arms, connected at elbows.

Ont pitch, nineteen lads threw meaty thighs intut muck. From nowhere, a ball coming at us, white missile flying through sleet. We scattered like pigeons. Ball smacked one of us square int tit, knocked down, winded. Circle of mud on white T-shirt like a target, like a brand.

Lad who scored pulled his T-shirt ovver his face, streaked across field wi his arms outstretched like Fabrizio Ravanelli.