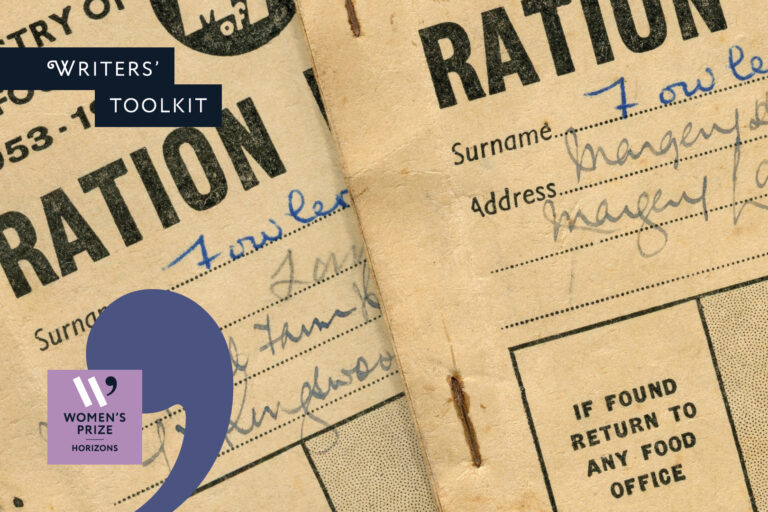

Primary sources, the records and newspapers created in the historic time you are writing about, are the fabric and basis of your research and the foundation of a solid non-fiction writing project. However, when writing non-fiction, one of the main challenges you face is how to seamlessly incorporate primary sources into the narrative. Findmypast, sponsor of the 2025 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, brings you practical advice on how to do it.

Finding Relevant Primary Sources

The first challenge you face as a non-fiction writer is finding and collating a corpus of relevant primary sources that will ensure the research for your writing project is robust. Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to research projects, which means you need to comb through and collate thousands of online repositories and sites to locate appropriate materials for your project. The breadth of records and newspapers housed in Findmypast makes it an unmissable starting point, as it allows you to refine your research—something you can learn more about in our previous guides: Using Records for Your Non-Fiction Research and Unlock Your Research with Newspaper Archives.

Incorporating Sources Seamlessly

But what happens next? How do you make the jump from finding significant records to embedding them into your writing? Some sources contain unexpected details that breathe life into your text, offering physical descriptions and glimpses into people’s appearances, attire, customs, and everyday life, and provide an excellent starting point to describe key aspects of a period.

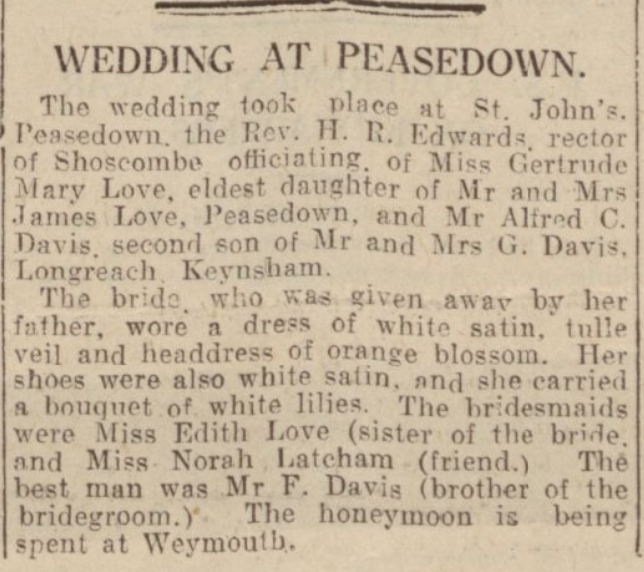

For example, while exploring regional news about the Love family in Somerset, you learn that one of the daughters, Gertrude, was married in 1933, ‘charmingly attired in a dress of white satin, a tulle veil, and a head-dress of orange blossom’, complete with matching satin shoes. This snapshot provides fascinating insights into wedding fashion, material culture, and customs of the time that you could incorporate into your work.

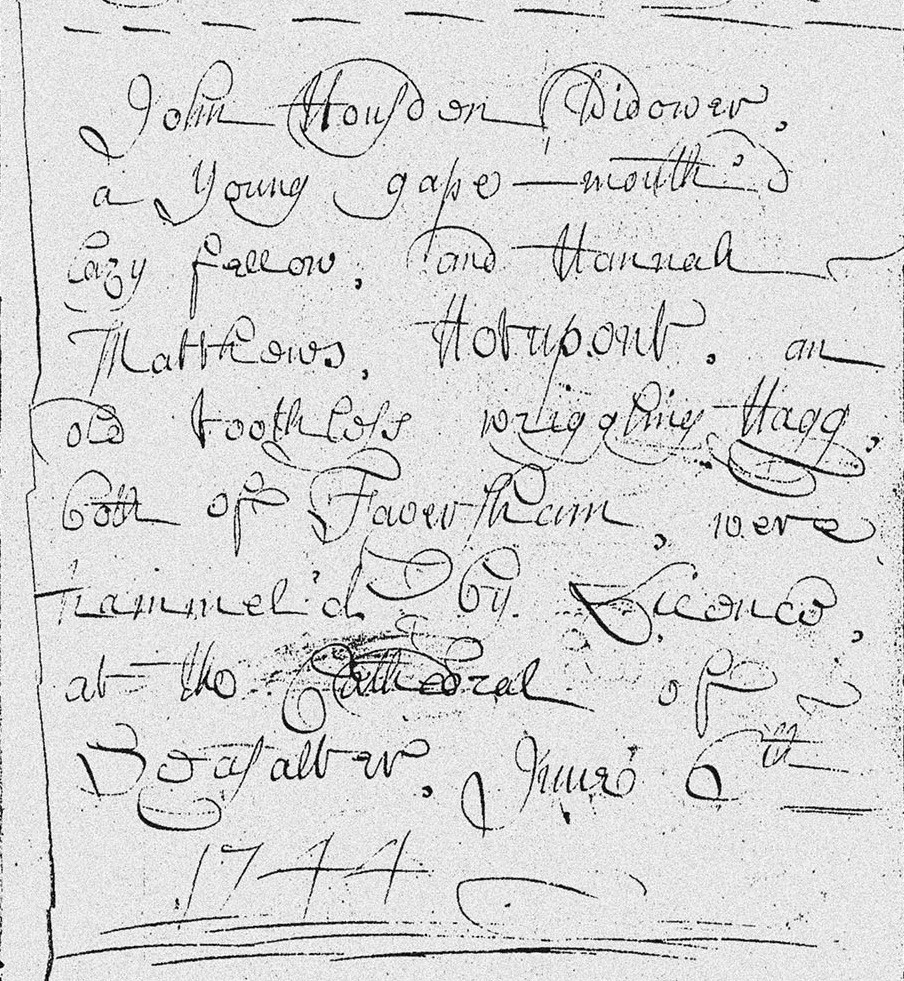

Primary sources can also provide insights into the attitudes and language of former times. For example, an entry from a 1744 marriage record created in the Archdiocese of Canterbury offers a curious portrayal of a newlywed couple: the groom is described as a ‘gape-mouth lazy fellow’, while the bride is referred to as a ‘toothless wriggling hag’. As you engage with these historical perspectives, you are forced to confront the moments of repression, abuse, and marginalisation that often seep through the pages.

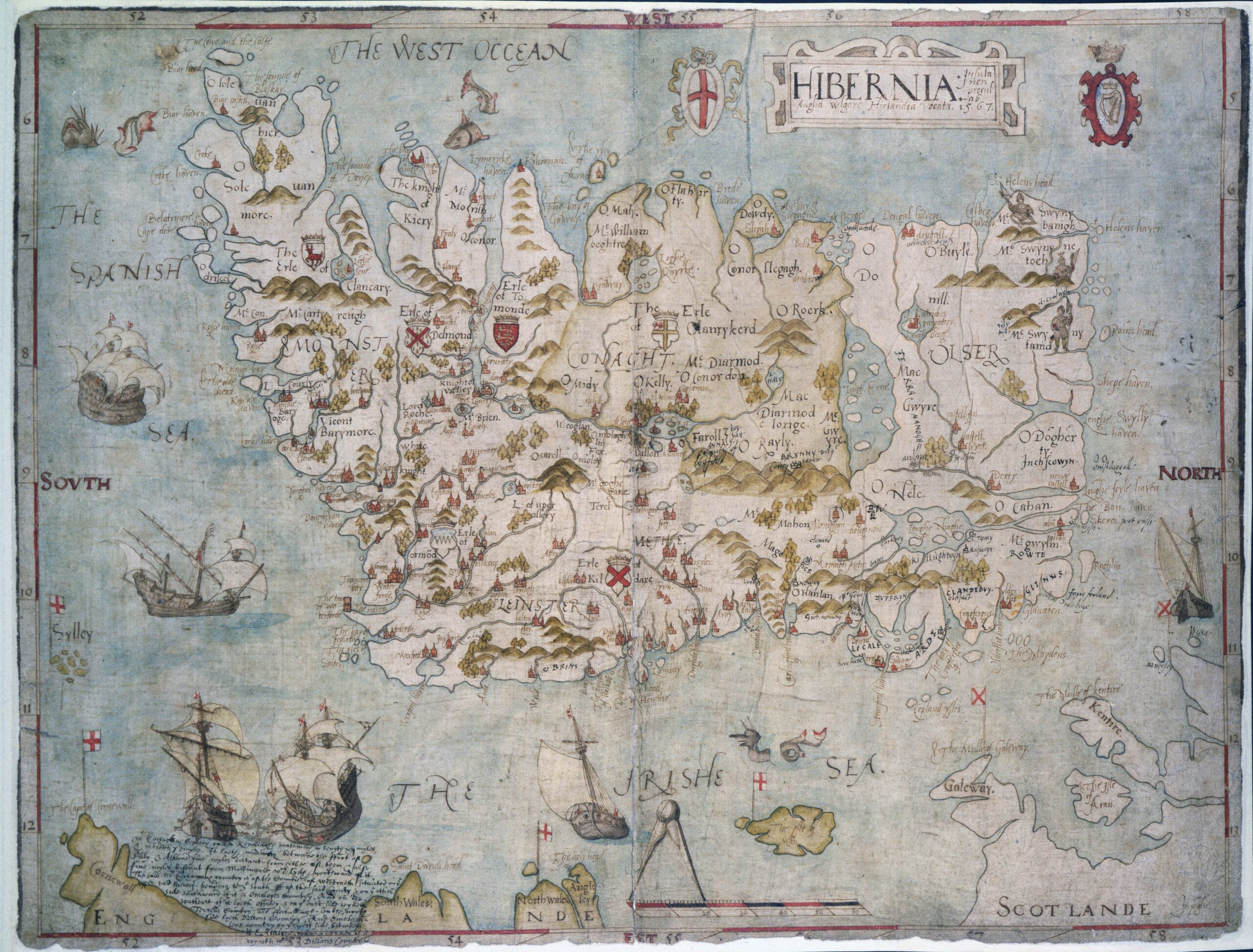

Historical maps are another excellent resource for informing your research, offering valuable insights into places that may have been profoundly transformed over time. The map below presents an early 16th-century depiction of Ireland. Exploring such maps can deepen your understanding of the setting and provide a fascinating window into 16th-century cartography.

Primary sources offer both the beauty of unexpected, sweet details and the stark contrast of historical struggles. That’s why it’s crucial to maintain a critical attitude and question why, how, and by whom a source was written in the first place.

Conclusion

Incorporating primary sources into your research and writing can feel like an intimidating task, but it’s also one of the most rewarding parts of the process. Whether you’re uncovering untold stories, exploring local histories, or bringing forgotten narratives to light, Findmypast provides records and newspapers to help you contextualise and deepen your narrative.

Dr Paula Del Val Vales is a medievalist and Editorial Associate at Findmypast, where she explores the intersections of historical research, archival work, and storytelling. Passionate about making history accessible and engaging, she has published articles and book chapters on the lives of medieval women.